7 Tips for Effective Classroom Communication (Mindful Language)

One day, I was in my yoga room awaiting my next class of students who were running late. Outside, I heard their teacher yell “Stop it right now! I cannot believe you. If you are not going to act right, you don’t deserve to be in yoga class today. Do you want me to have to call your mother? Because I swear I will!”

As I approached my class of kindergartners, struggling to get into or stay in their assigned “boys” and “girls” lines as they waited to enter the room, the tension and discomfort hung thick in the air. I felt knots forming in my own stomach as I noticed some children staring at the floor, some watching me nervously and some, seemingly oblivious to the trouble, spinning and bumping into one another.

The teacher gave me an aggravated look…a mix of anger and resignation.

What could I do?

How could I create a space of safety, belonging and ultimately learning in that moment?

I wish I could say that this was an exception but it’s not. As class sizes and academic expectations increase, children’s needs expand, and teacher support and resources dwindle, effective classroom communication is often the victim of authoritative methods involving power struggles and threats.

This type of communication may provide short-term gains and a semblance of control but it is also unsustainable and ultimately harmful to all involved.

The Reality of Classroom Management

A google search of the term Classroom Management yields over 460 million results…this topic is so broad and overwhelming, it is hard to know where to even begin. Sadly, many classrooms are plagued with communication strategies that could benefit from more mindful language. Three of the realities that plague classrooms include:

1. Fear-based Communication

Teachers want to assert more influence and control over children’s behavior, often in service of rigid daily schedules and mounting academic pressures. Teachers also want to keep children safe and therefore have rules in mind, whether or not the children are actually aware of them.

The kindergartners in this scenario had strayed from their lines, and one had almost gotten pushed down the stairs. That must have been scary for the teacher. And as any parent will likely admit, our best communication does not happen in moments of fear.

2. Inconsistent Rules

Sometimes teachers methods or rules are inconsistent which means children do not know what the expectations are “right now.” Also, authoritative language does not support children in learning to self regulate, or encourage them to have agency in their own learning.

Therefore interactions with teachers become oppressive, and students are required to behave or obey…the consequence of misbehavior being punishment and sometimes even public shaming. Consequences are not explained, and children do not have the logical reasoning by which to understand them.

3. Problematic Communication

Children begin to question their value and ability, and may even modify their effort or their willingness to risk an incorrect action or answer, for the sake of not being put down. The way we communicate can ultimately lead to the development of either a fixed or growth mindset, the latter being necessary for success.

The consequences of these communication styles are varied, but generally children become motivated by a combination of external judgement and fear. Some become praise junkies…

These are the students that constantly ask “Was I good? Did I do a good job?” instead of being focused on what they are learning. They value results only, rather than being excited by effort and process.

Examples of problematic communication:

Comparisons: Teachers say they want a child to be “more like Person X” or “less like Person Y”. “I like the way that Person Z is sitting right now.”

Power struggles and threats: “You had better listen to me.” “I’m going to call your mother.” “No recess for you today!,” “Don’t you dare!"

Vague or Judgment-Filled Language: “Good job,” “You’re so smart,” "Are you kidding me?” etc.

“In a growth mindset, challenges are exciting rather than threatening. So rather than thinking, oh, I’m going to reveal my weaknesses, you say, wow, here’s a chance to grow.”

Children, like many adults, live in constant comparison with others. When they are haphazardly, and incorrectly, identified as “the problem child” or “the good one,” a “trouble-maker” or “brilliant” by the teacher, they absorb and use these labels about each other and themselves.

When teachers categorize children both consciously or subconsciously, it can also effect the amount and quality of attention they give certain students.

How to Foster Effective Classroom Communication with Mindful Language

Though it may seem daunting at first, effective classroom communication is absolutely attainable — and using mindful language in the classroom and with children can help us get there.

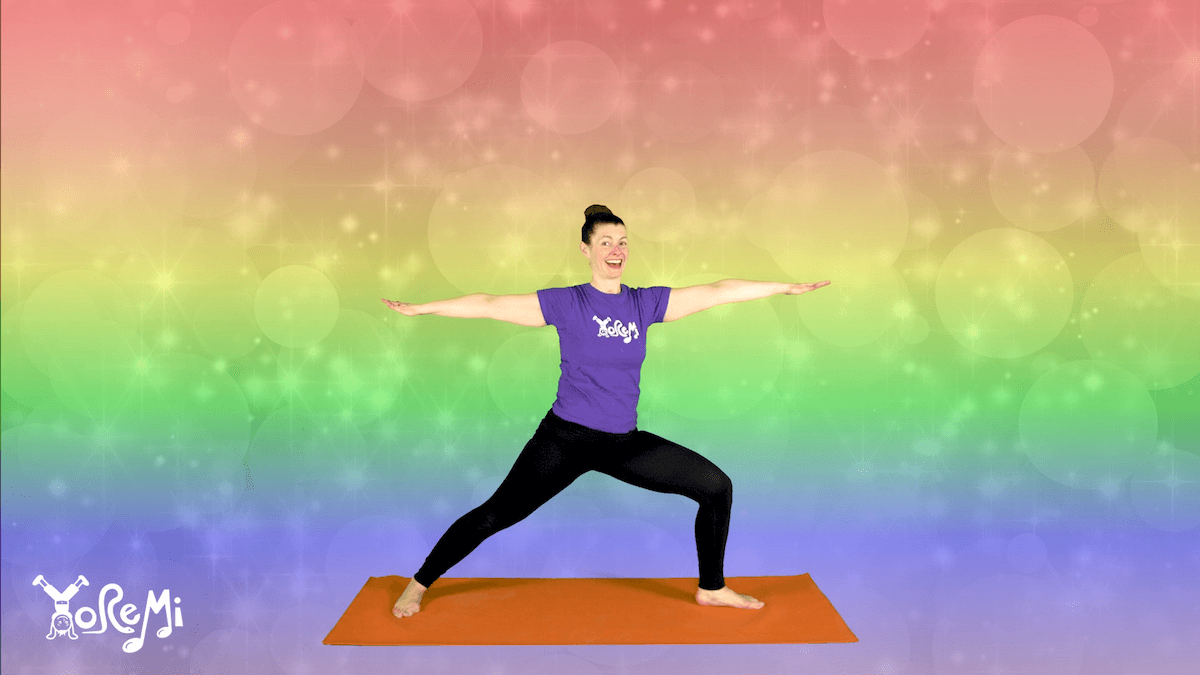

In Yo Re Mi classes, for instance, we encourage:

Children and teachers to act in collaboration

Creating a safe space

Teachers to use inclusive language

Teachers to ask open-ended questions

Sharing and valuing the ideas of others

Everyone to listen

Teachers to use fact-based observations instead of praise

Communicating logical consequences of classroom behavior

Not that we’ve reviewed the realities of classroom management, here are tips on implementing effective classroom communication using mindful language approaches.

1. End the Power Struggle with Collaboration

When teachers and students act in collaboration, it up-ends the typical top-down power structure of a classroom environment. Teachers and students become active and equal members of the learning community.

For teachers, this requires a sometimes unusual amount of presence, creativity, patience, mindfulness and a willingness not to be “in control.” For children and teachers both, this requires a lot of reflection, assessment, and listening to collaborators.

Mutual respect does not always occur immediately, but will develop with commitment and modeling from community members. Learn more tips for setting up the classroom for success.

2. Create a Safe Space

Collaboration sets the groundwork for self-regulation and co-regulation. Start with an icebreaker activity around teamwork and invite the students to create classroom rules together. Children are much more likely to adhere to agreements they generated themselves.

Once established, the group dynamic will support children who deviate from those expectations to re-align, sometimes without any teacher involvement.

Encourage the children to develop class agreements by asking thoughtful, open-ended questions:

“What can we do to make our best learning happen here?”

“How can we keep our bodies very safe in this space?”

“What will we do when our friend is sharing an idea? What will they do when we’re sharing?”

“What is one way we can signal that we have an idea without shouting?”

Make these guidelines well-known, and apply them consistently for all classes and students.

My favorite icebreakers often involve singing and moving together. The seated movements in Making a Pizza are perfect for morning meeting or circle time and invite children to collaborate and share ideas. Here are more mindful icebreakers for the classroom and fun kids songs that encourage teamwork.

3. Foster Belonging with Inclusive Language

Inclusive language doesn’t leave anyone out. Make sure to place emphasis on inclusive group labels for children. Saying, “Okay guys!” might make someone feel un-included. Instead, say, “Okay children!” or “Okay friends!”

Avoid closed questions which can be answered “yes or no” as they can hinder the group momentum or stifle creativity. Encourage participation without needing to make it competitive of comparative.

Keep the activity or lesson moving with a lot of WE and US. Keep your language inclusive, repetitive, and positive!

Examples of exclusionary language are:

Can you bend your knees to make your body like a chair?

Would you like to visit Alaska today?

Who is the tallest mountain today?Modified inclusive versions are:

Bend your knees and reach arms up. Look, we are chairs!

Let’s go to Alaska! How will we get there?

I’m a tall mountain. You be one too. Let’s say it together, “I’m a tall mountain.”

One of our favorite ways to model inclusivity and create belonging is to gather in a circle. In a circle, we can all see one another and everyone is on the same level (including the teachers).

Everyone is welcomed, included and has agency in creating and directing the group dynamic. As teachers, we acknowledge that we have just as much to learn from the children as we have to share with them.

Try this: Breathing Ball Name Game

Pass the breathing ball around the circle. Each child takes a turn saying their name, how they are feeling today and then leads the group through one inhale and exhale with the breathing ball.

Read more about our favorite activities for creating belonging for children and their grown-ups.

4. Share Ideas and Validate Experiences

Once we have up-ended the top-down approach to learning, it should be made very clear that children’s ideas are welcome and encouraged in the class. When we create space for the unique and often unpredictable contributions of children, the learning takes on a life of its own, with everyone playing a role in discovery and inquiry.

Once your class determines how to share ideas collaboratively, we want to SAY YES to those ideas as much as possible. Here are some examples of how sharing ideas might work in a Yo Re Mi class:

example 1: “We have decided that in this class, if you want to share your idea, you will place a quiet finger on your nose. If I see you doing that, I’ll know you want to share an idea, and I’ll invite you to share it.”

example 2: As we discuss traveling to our destination, a student gives the “idea” signal. When called upon, the child says, “Let’s take a monster unicorn super jet!” The teacher as facilitator might say “Yes! I have never seen that before. Can you describe it?” OR “Great! How do you make that with your body?”

Get a few ideas from the children, combine them into a movement sequence and make up a simple two-line rhyme. “Monster Unicorn Super Jet. That’s something we won’t forget!”

Invite the class to invent the sound of a monster unicorn super jet engine. Is it a high or low sound? Loud or soft? Someone makes a lip buzzing sound. “Great! Let’s all try that!”

5. Teach and Model Listening Skills

In order to share our ideas, maintain safe space, explore the lesson, and keep the inquiry flowing we have to make sure we are all listening. This means absorbing our friends contributions as well as being able to follow directions from a teacher or classmate.

Here are some of our favorite exercises that encourage listening. These are great for gathering activities and to re-focus our collective energy when needed.

“I Say, You Say” On rhythm, begin a series of short syllables or words that the children will repeat. Keep changing it and see if they can follow.

“Count the Taps” Teacher will clap or play a number of taps on rhythm sticks or tambourine. Using no words, the children will count the number of taps, and put that many fingers in the air. Perform the tapping several times, encouraging the children to really listen and try to figure it out. Then, put hands down and ask the children to count it out loud with you.

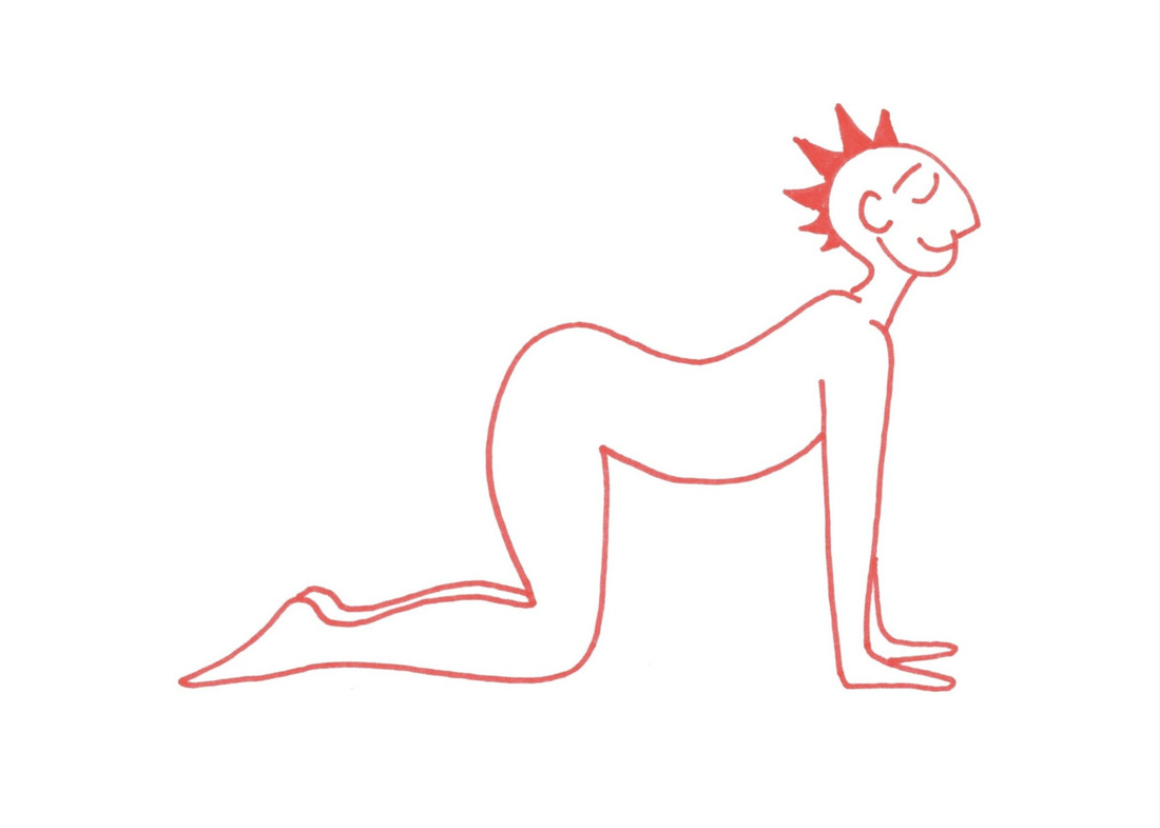

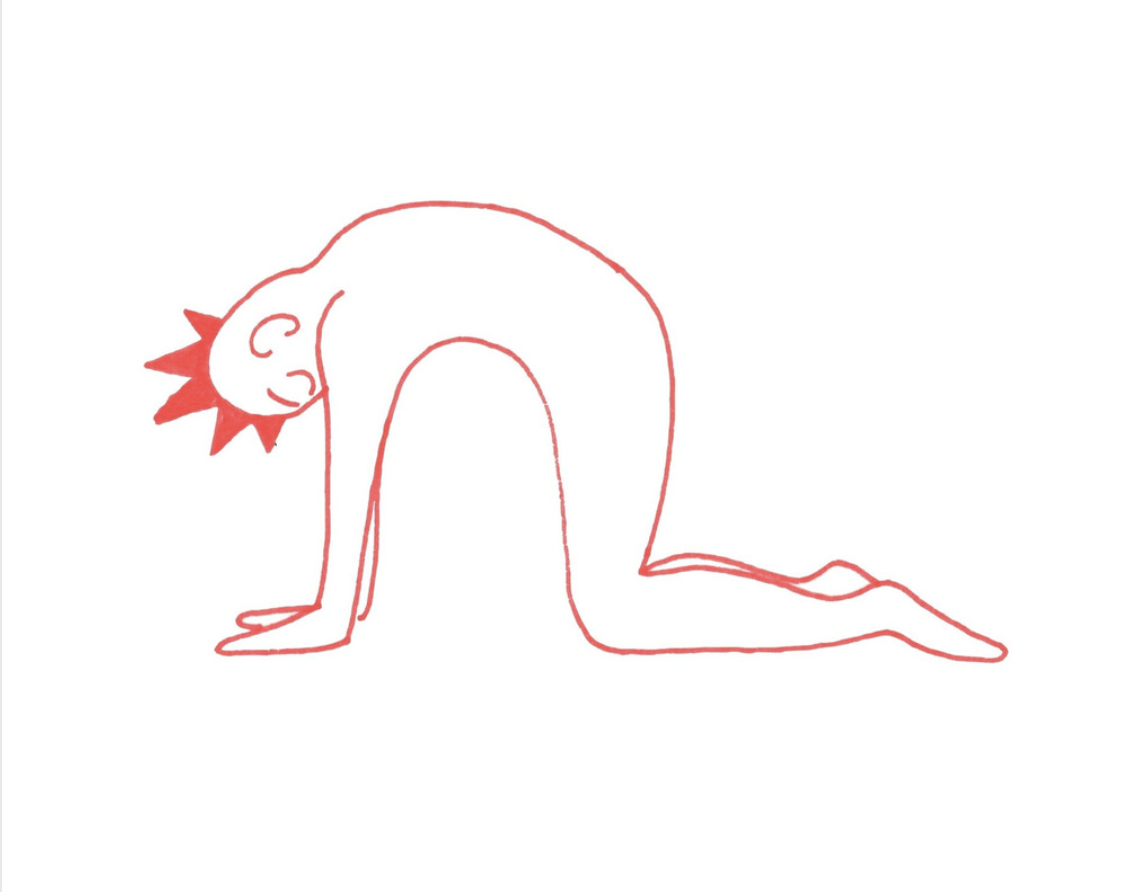

“Chime Listening” Three steps that increase in complexity. First, ask children to close their eyes, and when they hear the chime, open their eyes. Second, ask children to rest in child’s pose, and when they hear the chime, do a yoga pose like mountain or down dog. Third, repeat the second pattern, but have them stay in the pose until the chime ring ends, and then go back to child’s pose. You can also do the entire three part pattern sitting, using a cross legged forward fold, boat pose, and sitting cross-legged.

“Find The Rhyme” (inspired by Johnny Richardson’s song) Come up with an interesting story where you leave the last word of the line out. The children have to guess the rhyme.

Example: “I went to Lily’s house one day, and I said would you like to go out and ____? (play!)” Perhaps tell a story that lines up with your day’s theme.

Sing along with Dan to Sittin’ on the Floor, a fun call-and-response listening game. Once you are familiar with the pattern, you can have the children add sounds and movements of their own or take turns leading the exercise.

6. Fact-Based Observations Instead of Praise Language

Most of us have been raised on praise language…we are part of the “Good Job” generation and are passing that along to our children and students. While we want to recognize effort and encourage certain behavior, saying “Good Job” can actually do the opposite.

Take a moment to ask yourself…what does good job even mean? It is vague, judgmental and doesn’t recognize the behavior you are witnessing. Therefore children often do not even know what they did to earn your praise.

In addition, because of the vague nature of this phrase and others like it, young children have a difficult time discerning “Good job” from “I’m good.” Instead of shining a light on their effort, process, resilience, creativity, etc. we instead help them create a value judgment about themselves.

The child that struggles and doesn’t often hear “Good job” may even internalize “I’m bad.”

In order to maintain a non-competitive environment, where children feel safe, and no one feels excluded, we must exchange praise language for fact-based observations, which encourage self-reflection without judgment and help a child to value their own effort.

A fact-based observation is a statement that reflects something observed….just the facts. For example, a child shows you his drawing. Instead of saying “Good job” or “That’s so pretty” you might say “I notice you used many colors in your drawing” or “I saw you working on this for a long time. That takes a lot of concentration and focus.”

The teacher becomes a mirror, where a child can deepen their understanding and recognition of their effort and skill, building intrinsic motivation and growth mindset. Learn more about fact-based observations in the second part of this three-part series.

7. Employ Logical Consequences

Everyone makes mistakes. Learning to walk in the classroom instead of run, or to share materials, or to use appropriate voice levels can be a positive experience and doesn’t have to involve a power struggle.

When expectations have been made very clear, logical consequences can help keep a class activity orderly and safe. When a child forgets or chooses not to follow rules, it’s the teacher’s job to help them identify a better course of action, resolve any conflicts and help them feel safe and respected. There’s never any shaming involved.

“It’s a powerful way of responding to children’s misbehavior that not only is effective in stopping the behavior but is respectful of children and helps them to take responsibility for their actions…The goal of logical consequences is to help children develop internal understanding, self-control, and a desire to follow the rules.”

We take logical consequences a step further and employ them as a response to all behavior, not just misbehavior. This helps children understand the positive results of their actions on their learning and on the group dynamic. Once we have mastered fact-based observations, we can use them to show children how their efforts contributed to positive consequences.

For example, a teacher might say “Everyone helped clean up before circle time which made it happen super fast. I saw you all working together. Because of that, we have time to sing two extra songs this morning!”

It is often most helpful to take a child aside and address disruptive behavior privately, using both fact-based observations and logical consequences.

Take the time to collaboratively set an agreement about what acceptable behavior looks like before the child returns to the group. Taking time out of any activity is never punishment but rather an opportunity to regroup and create a strategy for inclusion.

Effective Classroom Communication Requires Mindfulness for Teachers

All of these communication strategies require an immense amount of presence from educators. And let’s be honest, many school environments do not make this level of engagement easy.

Classrooms are often overcrowded and understaffed, schedules are rigid and packed, and academic pressures are high.

We start with the best of intentions only to find ourselves slipping into survival mode much of the day. Ultimately, we know these strategies will improve the classroom experience, but implementing them requires a high level of institutional support and personal growth.

We know that teaching is rated one of the most stressful occupations in the US. To combat the burn-out, emotional fatigue, and self-regulatory exhaustion that can accompany the day-to-day chaos of a classroom, teachers need their own mindfulness practices (we have a two part guide on mindfulness for educators). Change starts from within and then ripples out into our classroom, family and community.